Haq Movie 2025’ and the Shah Bano Verdict: What Every Indian Should Know About Muslim Women’s Rights

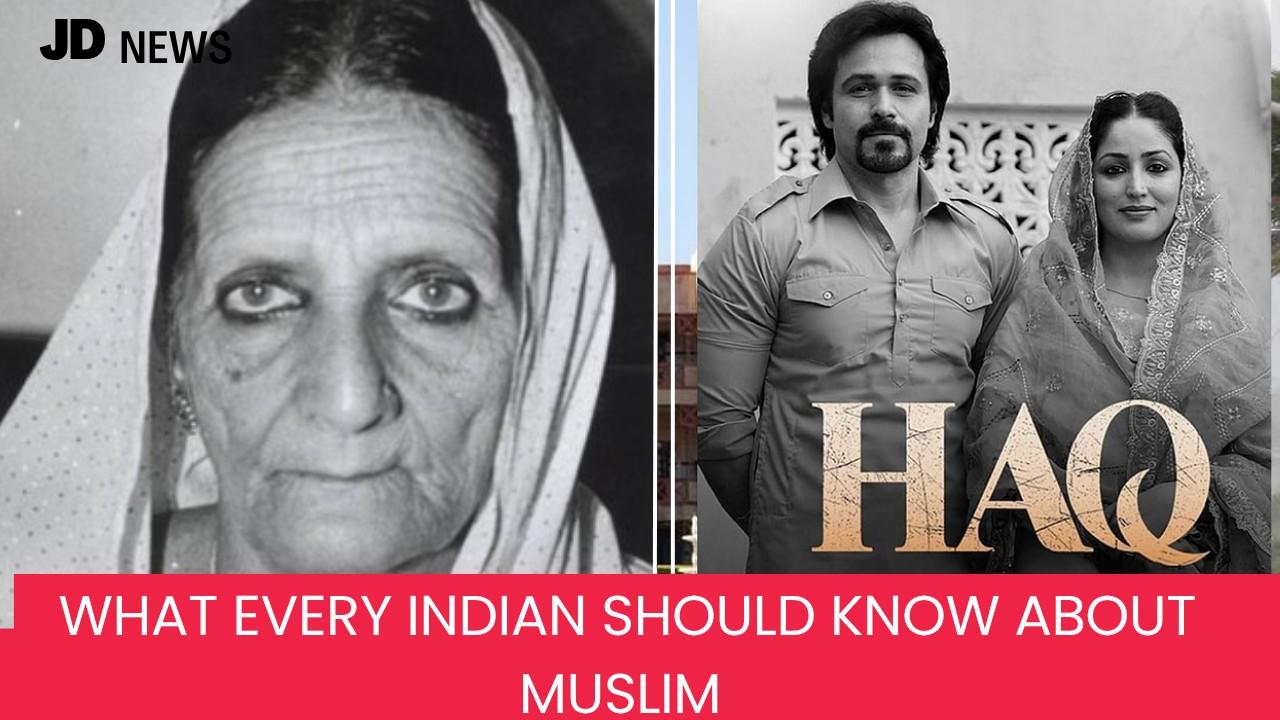

The upcoming Bollywood film Haq, starring Yami Gautam and Emraan Hashmi, has reignited public interest in one of India’s most pivotal legal battles — the 1985 Shah Bano case. Scheduled for release on November 7, 2025, the film revisits the story of a woman who dared to challenge the boundaries of religious personal laws, advocating for her right to maintenance after divorce. Beyond the cinematic narrative, the Shah Bano case continues to be a touchstone for debates surrounding Muslim women’s rights, secularism, and the need for a Uniform Civil Code (UCC) in India.

The Shah Bano case began in April 1978, when a 62-year-old Muslim woman from Indore petitioned for maintenance from her husband, Mohammed Ahmad Khan, a well-known lawyer. The pair married in 1932 and had five children together. Fourteen years into the marriage, Khan abandoned Shah Bano, married a younger woman and cutting all links with his first wife and their children. When Shah Bano was left without financial assistance, she cited Section 125 of the Criminal Procedure Code (CrPC), 1973, which requires a husband to provide maintenance to a wife who is unable to support herself. The case was about more than simply money; it was about dignity, justice, and fighting biassed interpretations of personal law that frequently exposed women.

The term iddat, which refers to the mandated waiting period that a Muslim woman must observe after divorce or the death of her spouse before remarrying, was important to the case. Khan's defence mentioned this time period, which is usually three months or until childbirth if the woman is pregnant. Khan contended that his obligation to provide financial support was limited to the iddat period, citing the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act of 1937, which barred courts from meddling in Shariat-governed matters. The All India Muslim Personal Law Board agreed, claiming that maintenance responsibilities under civil law could not supersede religious law.

In 1985, the Supreme Court of India issued a momentous decision following a seven-year legal fight. Chief Justice Y. V. Chandrachud maintained the High Court's ruling and granted Shah Bano alimony under Section 125 of the CrPC. Justice Chandrachud's decision emphasised that legal safeguards were not religiously bound: "Neglect by a person of sufficient resources to sustain these and the inability of these persons to maintain themselves are the objective elements that determine the applicability of section 125. Such provisions, which are primarily preventative in nature, transcend religious boundaries. This decision not only granted Shah Bano support, but it also overturned long-held conventions in Muslim personal law, demonstrating that gender justice transcends religious precepts.

The decision, however, sparked a political uproar. Prominent Muslim organisations condemned the Supreme Court's ruling, claiming it violated religious freedom. The verdict caused the then-Congress administration to pass the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act of 1986, which restricted support claims to the iddat period. While intended as a compromise, the law was criticised for eroding women's rights, driving many divorced Muslim women into financial dependence, and emphasising the persistent conflict between personal rules and constitutional guarantees of equality. Shah Bano gradually faded from public life and died in 1992, her struggle recognised as one for dignity and self-respect.

The case has far-reaching ramifications beyond one woman's predicament. Shah Bano became a symbol of resistance to personal law's systemic gender inequality, as well as a catalyst for broader discussions about minority rights, secularism, and the UCC. Her bravery sparked later judicial battles by women demanding maintenance, property rights, and protection from unjust treatment. The case's political, social, and legal implications continue to affect discussions on Muslim women's rights in India.

Haq revisits this historical conflict from a contemporary perspective, highlighting courage, tenacity, and the quest of justice. It is also being scrutinised by Shah Bano's family, who claim that it is appropriating her identity without her legal consent, highlighting persistent concerns about personal stories and portrayal. The film, starring Yami Gautam, strives to teach a new generation about legal knowledge and gender justice by combining cinematic storytelling with social criticism.

As India continues to struggle with the balance between personal laws and constitutional rights, the Shah Bano case remains a cornerstone in understanding the growth of women's rights. It reminds citizens that legal wins are difficult to achieve, frequently politically challenged, and inextricably linked to societal attitudes about gender, religion, and justice. Haq is more than just a film; it reflects on a watershed moment in India's democratic and judicial history, as well as a call to continue the conversation about equality and empowerment.

Disclaimer: The information provided in this article is for general guidance and educational purposes only. It is not intended as legal advice. Readers are encouraged to consult legal experts for professional guidance regarding personal laws and rights.